On May 13th 2021 the Uyghur Human Rights Project and Justice For All’s Save Uyghur Project issued a 77-page research report outlining what is happening to Imams under the Chinese persecution of the Uyghur people. So far 16,000 masjids have been demolished in Eastern Turkestan and the fate of Imams is extremely difficult to determine. However, it is safe to say that China has imprisoned or detained at least 630 imams and other Muslim religious figures.

BBC Report: Uyghur imams targeted in China's Xinjiang crackdown

“The UHRP, working with rights group Justice for All, tracked the fates of 1,046 Muslim clerics — the vast majority of them Uyghurs — using court documents, family testimony and media reports from public and private databases.”

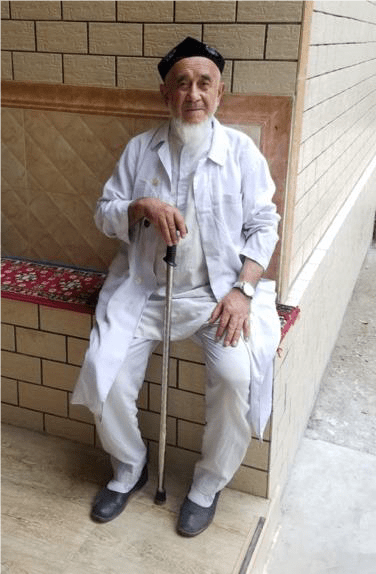

Imam Abidin Ayup

Abidin Ayup is a respected religious leader and former imam of the Qayraq Mosque in Atush for around 30 years, and worked as a professor at the Xinjiang Islamic Institute before retiring around 20 ago. He is over 90 years old.

Available evidence shows that he was likely detained in a camp sometime between January and April 2017. A court document refers to him as an inheritor of religious extremist thought and a key person for reform through education suggesting that he was detained for his religious background. The court verdict also indicated that he was already in poor health as of May 2017.

According to testimony to the Xinjiang Victims Database, he is presumably detained in Kizilsu.

Imam Ahmet Metniyaz

Ahmet Metniyaz was the imam of Langer Mosque of Aksu city and a well-known Uyghur religious scholar who was once the general secretary of Aksu Islamic Religious Association.

In 2015, the regional government awarded Mr. Ahmet a model of ethnic unity and progress prize by regional government, and regularly quoted him in the Chinese press supporting government policies regarding religion.58 He was also one of 90 religious scholars who were received by the regional Party Secretary, Chen Guanguo, on November 30, 2016, where he gave a speech with eight other scholars and imams.

According to witness testimony, he was sent to a camp at the beginning of 2017, and at the end of 2017 was sentenced to 25 years in prison on unclear charges.

Summary Findings

Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in East Turkistan (also known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China) have long endured repressive Chinese government policies targeting their cultural identity. Religious leaders in particular have been frequent subjects of state-directed abuse.

This report presents new evidence detailing the extent to which Uyghur religious figures have been targeted over time. Using primary and secondary sources, we have compiled a dataset consisting of 1,046 cases of Turkic imams and other religious figures from East Turkistan detained for their association with religious teaching and community leadership since 2014.2 The total cases in the dataset should not, however, be construed as an estimate of the total number imams detained or imprisoned. The total cases we have reviewed likely represent only the very tip of the iceberg, given severe restrictions on access to information.

Of the cases in our dataset, 428 (41%) are individuals who have been sent to formal prisons (including 304 sentenced to prison terms), 202 (19%) have been detained in concentration camps (reeducation centers) and have died while in detention or in prison, or shortly thereafter. We reviewed many more cases of alleged detention that lacked important case details.

The dataset shows that the government has targeted mostly male Uyghur religious figures born between 1960 and 1980. However, a sizable minority of Kazakh Islamic clergy of roughly the same demographic group have also been detained, as well as several Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Tatar figures, indicating the breadth of persecution. Up to 57 cases in our dataset (5%) concern individuals over the age of 60.

The high rate of prison sentences (versus shorter-term camp detentions) in the dataset offers clues about the target and motivation of Chinese government policy in relation to religious figures. That 41% of the individuals in our dataset have been given prison sentences illustrates the intention of the Chinese government not just to criminalize religious expression or practice, but also to consider imams criminals by virtue of their profession.

Many of the cases indicate that government definitions of illegal or extremist have been ambiguous for years likely purposely so. As a result, Turkic clergy in East Turkistan have been sentenced to prison terms for quotidian religious practices and expression protected under both Chinese law and internationally recognized human rights treaties.

Grounds for imprisonment in the cases we reviewed include illegal religious teaching often to children prayer outside a state-approved mosque the possession of illegal religious materials, communication or travel abroad, separatism or extremism,5 and officiating or preaching at weddings and funerals, as well as other charges that simply target religious affiliation. The dataset includes cases of prison sentences of 15 years or more for teaching others to pray studying for six months in Egypt and refusing to hand in a Quran book to be burned as well as a life sentence for spreading the faith and for organizing people.

Some of those detained were once formally sanctioned by the government to serve as imams suggesting that the imams criminality is the result of a policy reversal Several cases also indicate that the government applied retroactive sentences for alleged violations that took place years prior.

Our dataset also indicates a major spike in the sentencing of religious figures in 2017, tracking closely with available government data.6 Of the 304 cases we reviewed that included data on length of sentence, 96% included sentences of at least five years, and 25% included sentences of 20 years or more, including 14 life sentences, often on unclear charges.

In addition to compiling and collating detention data, we also interviewed Uyghur imams outside of East Turkistan, as well as the son of an imam currently in detention. Our interviewees revealed details of harassment and persecution spanning several decades for their role serving their local congregations. The imams described facing varying degrees of persecution beginning in the 1980s until they fled the region in the 2015 and 2016 as a result of surveillance and the threat of detention. Their stories fill in many of the gaps in our understanding of the on-the-ground effects of Chinese government policies over time, as well as of forms of everyday resistance on the local level.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Chinese authorities in East Turkistan passed a proliferation of laws and regulations governing religion from the national to the local level, buttressing the new regulations with obligatory loyalty pledges, state-managed trainings, examinations, and enhanced oversight of imams in order to keep religious teaching under strict control. Uyghur-led protests in the 1990s, which resulted from restrictions on cultural practice, prompted the regional government to harden its policies even further, which led to a perpetuating cycle of domination and control well into the 2000s.

Imams we interviewed report having been persistently watched, followed, scrutinized, and directed in their work in the mosque, which escalated to a point where they felt that they no longer played a positive role in their work. All of our interviewees decided to flee East Turkistan because of relentless government policies and fears of possible detention. In 2017, the explosive growth in camps designed to arbitrarily detain and forcibly indoctrinate Uyghurs en masse confirmed those fears.

This report makes clear that imams and other religious figures, similar to members of the intellectual class in Uyghur society, stand at the very center of what one might describe as concentric circles of repression The government of the People’s Republic of China PRC has targeted religious leaders for decades. So, too, did pre-PRC leaders, given their discomfort with groups and identities that might compete with the influence of the central authorities. Whereas all Turkic peoples in East Turkistan have faced strict government controls in recent years, and whereas increasingly capricious government authorities are now willing to detain just about anyone, religious figures were targeted early and severely.

Chinese government efforts to detain and sentence Uyghur clergy have also taken place within the context of a state-led campaign to substantially modify or completely destroy religious and cultural sites like mosques, shrines, and cemeteries. Researchers have found that since around 2017, up to 16,000 mosques in East Turkistan (roughly 65% of all mosques) have been destroyed or damaged as a result of government policies with an estimated 8,500 demolished outright.7 At the same time, around 30% of all important Islamic sacred sites such as shrines, cemeteries, and pilgrimage routes have been demolished and another 28% damaged or altered, mostly since 2017.

As a result, even if imams have not been detained or forced out of their mosques, the physical destruction of their places of worship means that they have no place to preach or pray, given that religious practice at home has been prohibited. In the 1990s and 2000s, the Chinese government began confining religious practices only to mosques according to the law, only to later begin destroying the every mosques that served as the only legal spaces for religious practice.

In addition to placing harsh restrictions on imams and religious figures, and to destroying the physical spaces where they operate, the Chinese government has pursued an extreme campaign to prohibit nearly every Islamic practice foundational to the Uyghur people. In policy and practice, authorities have prohibited the teaching of religion at all levels of education; banned the use of traditional Islamic names like Muhammad and Medina for Uyghur children banned long beards for Uyghur men and headscarves for Uyghur women instituted an anti-halal campaign to prevent the labeling of food and other products as halal criminalized Hajj pilgrimage without government approval and adopted legislation broadly defining quotidian religious practices as extremist which a group of UN independent experts urged to be repealed in its entirety.

Representatives of the state also began purposefully humiliating imams and religious figures in recent years, including by forcing them to dance in public or participate in degrading activities like singing songs praising the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). 13 One imam interviewed by UHRP for this report corroborated this in his testimony, and shared that he and several hundred other imams were forced to wear athletic clothing and dance in a public square in 2014.

This evidence has been compiled by journalists, researchers, and experts, illustrating how Chinese government policy has been designed to eliminate core aspects of Islamic practice and expression. Chinese authorities have gone to great lengths, however, to ensure that some Islamic practice remains in East Turkistan as a means of demonstrating the government’s purported commitment to respecting normal religious activities The government boasts, or example, that it has strengthened the cultivation and training of clerical personnel by operating training institutes, but these schools have served, for any years, to maintain strict control over the imams and their teaching. Any expression of religious identity by Uyghurs in Chinese state media appears highly choreographed, repeating Party slogans and policies, and belies evidence presented in this report and elsewhere. What remains of religious practice among Uyghurs persists as merely a shell of its former self thoroughly dispossessed of the richness of Islam freely practiced elsewhere.

The Chinese government has targeted influential and knowledgeable Uyghur and other Turkic religious figures in a transparent attempt to halt the intergenerational transmission of religious knowledge in East Turkistan. By educing legal religious practice to only individuals over the age of 18 within the confines of state-sanctioned mosques led by state-sanctioned imams while firmly prohibiting teaching religion to children at home, while then later demolishing even some of those state-sanctioned religious structures, the Chinese government is extinguishing free religious practice in a single generation. Taken together, these policies will make it difficult if not impossible for Uyghurs to maintain any semblance of religious expression in the years to come.

The current campaign targeting Uyghur and Turkic people bears a striking resemblance to the horrors of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) as it was experienced in East Turkistan While policies and forms of repression in the two eras do indeed share some similarities, the scale and scope of what is happening today makes this current campaign of repression distinct, particularly thanks to the ability of the state to utilize sophisticated technologies to predict criminality and infiltrate even the most intimate unit of the family home. The Turkic population of East Turkistan is facing its darkest era in decades, and Uyghur religious figures have borne the brunt of repression.

The Chinese governments broad campaign to eliminate central aspects of the Uyghur identity, including religious belief and practice, likely amounts to genocide under international law. Rather than respond to calls to close the concentration camps and respect Uyghur rights over the last three years, Chinese leaders have doubled down and claimed that their approach has been completely correct Despite mounting criticism, Chinese authorities have indicated that they will forge ahead in this campaign, evidenced by the continued construction of camps, and the increasing use of widespread forced labor.

Although the international community has taken some small steps to respond to the repression, criticism has been mostly mild, if not entirely muted. Governments have an obligation to call out these abuses loudly and often. The Chinese government has been responsive, albeit defensively, to public statements of concern and condemnation, but like-minded governments who understand the implications of tacitly allowing this kind of behavior must cooperate in calling out the abuse. Without a robust response, the Uyghur identity itself in which religion plays a significant role will be under an ever graver threat.

Recommendations

To the People’s Republic of China

- Close the concentration camp system and release those detained, including all imams and religious figures;

- Cease the harassment and arbitrary detention of all Uyghur and Turkic imams and religious figures in all instances.

Release all Uyghur and Turkic religious figures arbitrarily sentenced to prison terms and provide information to the public regarding their cases; - Allow immediate access to an independent Commission of Inquiry and provide detailed records of arrest, detention, and imprisonment in vocational or re-education centers to those relocated for work placements and to those under house arrest;

- Immediately cease the destruction of all sites of cultural and religious value to the Uyghur people, including mosques, shrines, graveyards, and allow immediate reconstruction in consultation with the Uyghur population; and

- Remove limitations on the practice of religion for Uyghur children in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and expand the space for children to learn religion in various settings from family members and religious leaders.

To the United Nations

- Member States should establish a special session at the UN Human Rights Council to appoint a Commission of Inquiry to investigate human rights violations taking place in the Uyghur Region and develop strategies to end these violations;

- The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights should immediately make use of her independent monitoring and reporting mandate to investigate and gather information on the current situation in East Turkistan, and report to the Human Rights Council with her findings.

- The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief should send a letter to the Chinese government to urge the release of Uyghur and Turkic religious figures arbitrarily detained, and to urge respect for religious freedom in East Turkistan according to international standards;

- The Working Group on Enforced Disappearances and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention should send a letter to the Chinese government requesting detailed information on the cases of the imams and other religious leaders cited in the report; and

- The UN should engage in additional, cross-agency, multilateral action to press for accountability for religious persecution in China.

To national governments

- Publicly and privately urge the Chinese government, at every possible opportunity, to end its campaign of mass, arbitrary detention, and to release all those detained or imprisoned without due process;

- Appoint a religious freedom ambassador with expertise in China in order to respond to religious persecution across the country;

- Provide immediate support to members of the Uyghur community residing in your country who have been threatened, harassed, or intimidated directly or indirectly by the Chinese government, including by offering asylum or relevant legal documents;

- Work in cooperation with national governments and form, strengthen, and mobilize international coalitions to obstruct further rights violations targeting Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples; and

- Implement commitments on atrocity and genocide prevention through bilateral and multilateral diplomacy efforts, and independently investigate and make appropriate legal determinations regarding the treatment of Uyghurs and

other Turkic peoples in China.

To governments with Muslim-majority populations

- Substantively raise the issue of religious freedom for Uyghurs and other Turkic, Muslim-majority peoples in bilateral dialogue with the Chinese government, and urge the government to take immediate steps to reverse repressive policies targeting Islam;

- Publicly and privately urge the Chinese government to halt the destruction of mosques and shrines, and allow mosques to reopen;

- Urge the Chinese government to grant a government delegation unfettered access to Eastern Turkistan; and Organize public hearings including Uyghurs to help domestic populations better understand the situation in East Turkistan.

To civil society

- Support and amplify the voices of the Uyghur community abroad, particularly those missing, or unable to communicate with, relatives and friends in East Turkistan;

- Continue to speak out loudly in opposition to the treatment of Uyghurs in East Turkistan and abroad;

- Closely monitor developments in the human rights situation on

the ground in East Turkistan, and adapt and respond to new developments and trends; and - Support and collaborate with Uyghur-rights activists and organizations abroad to highlight the plight of detained religious figures, particularly through religious freedom and faith-based organizations.

What you can do with the Report

- Read it to educate yourself

- Share it with your elected leaders

- Donate for more reports to be developed